Knowing next to nothing about frugality, saving, and investing, the first two years of my career were a hilarious failure in terms of savings. I was going out to eat too much, too many nights out at the bar, buying stuff I didn’t need, and watching my money float way on the wind. I’d try to stash away whatever money was left over at the end of the month. This was a terrible way to save, of course, because, thinking I was Diamond Jim, my expenses would always expand to fit the month.

The result? Zero savings rate. I was also lazy and procrastinated – even when I was able to scrabble and save a few bucks, months would go by without adding it to my IRA or taxable account. My investment portfolio was growing slowly, in fits and starts. To be blunt, this was a half-assed way to save money. Then I got lucky. I stumbled upon some books – Your Money or Your Life and The Four Pillars of Investing – got smart, realized the power of FI, and learned how to save in a predicable, methodical way. And that’s when my savings started to take off.

The Key to Saving

Funnel money into your investment portfolio first and live off what remains. This forces you to save no matter what. And the only way to do this is to automate the process. We humans are lazy. If something requires effort each month, we’ll slack and delay and it won’t get done. But if it’s automatic, like using payroll deductions to fund your 401K, and direct deposit for your IRA and taxable accounts, then the money will flow into these accounts uninterrupted, week after week, month after month, year after year. And because it takes effort to stop or change this system once it starts, we’re more likely to do nothing and let it continue.

Start this automatic savings process with your first paycheck so you don’t get used to the money. It’s harder to automate savings if you’ve already built your lifestyle around your entire paycheck. You’ll need to unwind a lot of things in order to start saving. Inertia is powerful – if it takes work and is painful in the short term, most of us are unlikely to do anything and we won’t make the changes necessary to start saving.

First, Pay Off Credit Card Debt

First, use your savings to pay off credit card debt, if you have any, starting with your highest interest rate card. Don’t bother adding to a rainy-day fund or retirement accounts until you kill all your credit card debt. Remember, paying off a 20% credit card balance is like making a guaranteed 20% return on that money. It’s a no-brainer. What if you have an emergency and need some quick cash? You can always use the credit card again. And yes, your 401K match is like getting a 100% return, better than the 20% return of paying off your credit card. But that 401K money is tied up until you’re 59-1/2, while your credit card debt is an immediate emergency. Who cares about a 401K match that you’ll be able to tap decades from now, when you’re in danger of slipping into a credit card death spiral today?

Next, A Rainy-Day Fund

Next, you need a little rainy-day money. Deposit savings directly from each paycheck into a money market or short-term bond fund in a taxable account, until you can cover at least three months of bare bones expenses. That way you’ve got some room to maneuver if one morning you find your name plate removed from your office door.

Then, Maybe, Pay Off Your Student Loan Early

If you have a student loan, and the interest rate is high, say 5% or more, pay it off next. But if your student loan interest rate is lower than what you could make in the market, it makes sense to start funding FI before the loan is paid off, because you might be able to make 7% in the market, while your student loan interest is only, say, 4%, a net of +3%.

Then Start FI Savings

Once you have a three-month rainy-day fund, and your credit card debt (and possibly student loan debt) is paid off, start your FI savings. If reaching FI early is a priority for you, put half of your annual savings into your retirement accounts (401K and/or IRA) and the other half into a taxable account. The reason? Money in your retirement accounts is generally off limits until you are age 59-1/2. Money in your taxable accounts, however, is always accessible: there are no amount or age restrictions for either contributions or withdrawals.

For your retirement accounts, each year, first invest in your 401K (or Roth 401K if offered) at least up to the company match. This is free money, so be sure to max it out. Then fund a Roth IRA until you’ve reached the annual maximum ($5,500/yr as of 2015, with some restrictions for high earners). Still have “retirement account” money to invest for the year? Resume funding your 401K.

The best approach is to fund a Roth 401K, Roth IRA, and a taxable account simultaneously via payroll deduction and direct deposit, with deposits going straight into each account from each paycheck. Again, half in retirement accounts and half in taxable accounts if early FI is your priority. The nice thing about investing every two weeks is you never place a big chunk of money into the market at any one time – just a regular amount every two weeks, year after year, steadily building your investments.

How Much to Save and Invest?

At the start of your career, try your best to salt away at least 30% of your gross income. But the more, the better. Having just finished college, you’re not used to having money anyway, so you won’t miss it. And I promise you won’t have any regrets about reaching FI too soon. As your salary grows, keep your living expenses roughly the same as year one plus a little extra for cost-of-living increases and some fun, and save and invest a larger and larger percent, until your annual savings reaches 50% or more of gross pay. This is not Standard Path territory; we’re now on the Alternate Path. But realize it’s doable and will get you to FI within a short period of time – around 15 years.

The Math Behind FI

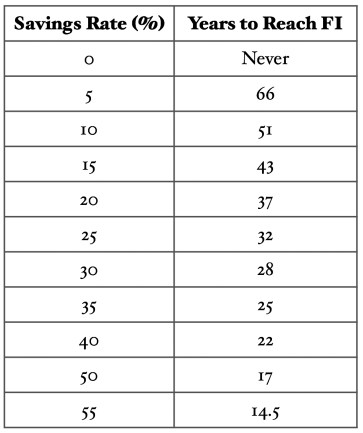

Why do I suggest ramping up your savings to 50%? Why not the conventional wisdom of saving 5%, 10% or, at the high end, 15%? Let’s look at the math behind FI. Your savings rate, as a percent of your gross pay, is the only thing that matters, because this single number captures all of the components of FI – how much you make, how much you spend, and your savings rate. Let’s look at how long it will take to reach FI at different savings rates, assuming a 5% real return and a 4% withdrawal rate. Although this analysis is simplistic, it does prove the overall point: you reach FI by earning a decent income, living modestly, and saving and investing a large percent of your gross pay.

In reality, things are more complex, and we may only be able to save 25% or 30% at the beginning of our career, when our starting salary is relatively low. But if we keep expenses modest and relatively constant as our income grows, our savings rate will grow as well, until we reach 50% or more. Saving more than 50% later in your career will offset the lower savings rate at the start of your career. The goal is an average savings rate of 50% of gross income during your working years.

Wage Slave at 0%, Independent at 50%

A few things to note about the above table. You’ll never reach FI if you spend every dollar you make (we’re ignoring Social Security for the moment). At a savings rate of 15% – the upper end of conventional wisdom – you’ll need to work for 43 years to reach FI, or until the standard retirement age of 65 if you start work at 22. The real magic happens at the higher savings rates. You’ll reach FI after just a 15-year career at a 55% savings rate. This is why I recommend savings rate of 50% if FI is a priority. Of course, not everyone is willing or able to save at these rates, but we should all be aware of the math.

The Most Important Thing

You may have noticed something important in this discussion. The most critical variable in reaching FI is your annual expenses. Everything flows out from this one number. You’ll also notice that my examples include annual expenses of around $20,000/year (per person, so around $40,000 for a married couple). You might scoff at this amount. That’s fine but think hard about what you’re giving up if you have an inflated lifestyle with high expenses. Would you rather live a simple, modest lifestyle that allows you to reach FI early and walk away from the Rat Race, or would you rather work until old age in order to support a more expensive lifestyle? The choice is yours. I like $20,000/year/person because it can support a modest, efficient lifestyle in most parts of the country, and allows for you to reach FI at a fairly early age, both of which are highly motivating for those of us that want to slip away from the work world.

Bottom Line?

Have money deducted straight from your paycheck – a minimum of 30% gross income to start, increasing to 50% or more over your career – and live off what remains. Can’t afford your house after savings are deducted from your paycheck? Sell it and buy a smaller place or rent. Can’t afford to buy a new car every few years because you’re now building up your investments? Buy a reliable used car and drive it for as long as possible. When you automate your savings and build your lifestyle around what remains, you don’t need to worry about having money at the end of each month to fund FI. This method forces all of us, even Diamond Jim, to save in a regular, predicable way.