So, where are we? By now, you’ve worked hard in school, landed a gig in a practical field that pays well, kept your expenses modest while still having a good life, and are automatically funneling money into your taxable account and retirement accounts. Plus you have a working knowledge of investing in stocks and bonds. But now it’s time for a big decision: how much should go to stocks and how much to bonds? What types of asset classes should you invest in?

The Most Important Thing

This is called your “asset allocation” which refers to your stock/bond split, and also the percentages and type of asset classes within your stock and bond mix – such as U.S. large company stocks, U.S. small company stocks, international stocks, Treasury bonds, corporate bonds, etc. This is a big decision. Why? Because asset allocation is the most important thing that you can control that will drive your long-term returns. We can’t control economic and world events, interest rates, or market returns, but we can control the percentage of stocks and bonds, and different asset classes, we hold in our investment portfolio.

One Shot at Retirement

A quick note: the investment philosophy around here is defensive investing, which means capturing market returns that are there for the taking by building a balanced, globally-diversified portfolio of inexpensive index funds that represent entire asset classes, and holding them for decades. This is the “slow and steady wins the race” approach. Offensive investors buy and sell individual stocks or hold a highly concentrated portfolio of just a few stocks, and their only goal is to beat the market. But for all this work, most fall short of the overall market return. Because we only get one shot at saving and investing for retirement, it’s smart to diversify our investments and not get too greedy. But I digress – back to asset allocation.

Risk v. Reward

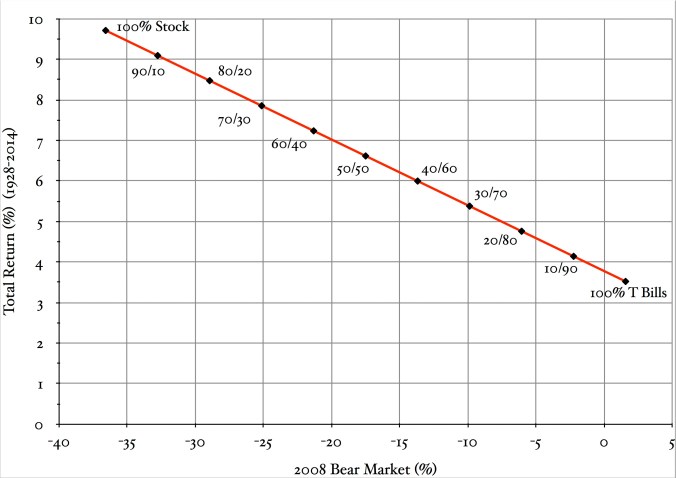

Look at the chart below, which shows long-term annualized rates of return versus the 2008 bear market for different U.S. stock/T-bill splits. For example, during 2008 a portfolio of 50% stocks and 50% T-bills lost about 17.5%. From 1928 through 2014, the 50/50 portfolio delivered about 6.6% annualized. Notice you’re losing annualized return in exchange for less severe, temporary losses during bear markets. So, the question is: How much can you tolerate losing (temporarily) in the course of earning higher returns? At what point will market losses cause you to lose sleep, panic, and abandon your long-term investment plans?

The relationship of risk versus return. An all-stock portfolio returned an annualized 9.7% from 1928 through 2014, but suffered great temporary losses along the way, such as a -36.5% return during 2008. An all-T bill portfolio fared well during 2008, but with a corresponding low long-term annualized return of about 3.5%. Want high returns over the long term? You must be able to weather frightening down markets along the way. Source: Standard & Poor’s; St. Louis Federal Reserve.

Dry Powder

Keep in mind that the real (inflation-adjusted) return of short- and intermediate-term bonds will likely be meager, especially in low interest rate environments. Cash for sure. You should view your bond and cash allocation as ballast against steep stock market declines, which will smooth out the ride of your overall portfolio, allow you to sleep a little easier at night, and give you some “dry powder” that you can use to buy stocks when they’re on sale. If you’re retired, short-term bonds and cash can also be used to pay living expenses during a down market, to avoid selling stocks at depressed prices. But again, don’t expect bonds to be a big money-maker. If you’re lucky, short-term bonds will likely just maintain their purchasing power over the long term.

The Big Picture

My thinking on the stock/bond split has evolved over the years. My thoughts today: if you are in the midst of your career, a 100% stock portfolio makes sense so long as you are educated in stock market history and don’t panic during the inevitable stock market declines. Why 100% stocks? Well, you don’t need to sell stocks to pay your rent or buy groceries – your earned income takes care of that for you so you can ride out the downturns. And over the long haul the expected return of stocks is higher than bonds. But be careful – if you haven’t lived through a major stock market decline, you don’t know how you’ll behave when it happens, even if you’re confident on paper. If you’re unsure about how you’ll react, add some short-term bonds to your portfolio, up to say, 30%, until you live through a 25%+ downturn and see how you feel (hint: it’s not fun).

As you get closer to retirement and/or are in retirement, make sure you have at least three years of annual expenses (net of dividend income and any other passive income) in short-term bonds or cash. Why? To avoid the need to sell stocks at depressed prices to raise money for expenses; this three-year cash cushion is the bridge between market highs. If the market declines, you can draw from this cash cushion to pay your expenses. This gives you time for the market to recover, at which time you replenish your cash cushion by selling some stocks.

Further Splitting

The heavy lifting is done once you decide on the stock/bond split. On the stock side, diversify into total U.S. market (60%), extended U.S. market (20%; these are mid- and small-cap companies), and total international stock market (20%). This is a “tax-efficient” allocation and will work well for both retirement and taxable accounts (we’ll discuss why in the next post). Plus, it’s dead simple. If you want to own bonds, keep it simple with a Short-Term U.S. Bond Market Index fund (which owns short-term, U.S. Treasuries (70%) and high-quality corporate bonds (30%). Short-term bond funds do well when the stock market goes to pieces, just when you need it the most.

A Parting Thought on Deploying Cash

If you have a bunch of cash on the sideline and are looking to increase the stock percentage of your asset allocation, consider deploying your cash at regular intervals over a span of, say, a year or two, until you’re at your target asset allocation. This will avoid dumping in a bunch of money right before a market decline and will help you sleep easier while you’re building your stock position. Of course, if the market really takes a dive during this period, go all-in with your remaining cash.